It’s late 2024. The war in Ukraine has ended. What should the world do now?

For the purposes of this opinion piece, we will assume that the most neutral possible terms have been reached. Borders are negotiated to the status quo ante bellum – that is, Russia retaining Crimea but agreeing to withdraw from all other annexed territories Putin claims.

Despite this resolution, countless decisions will remain for leaders in Washington, London and across European capitals.

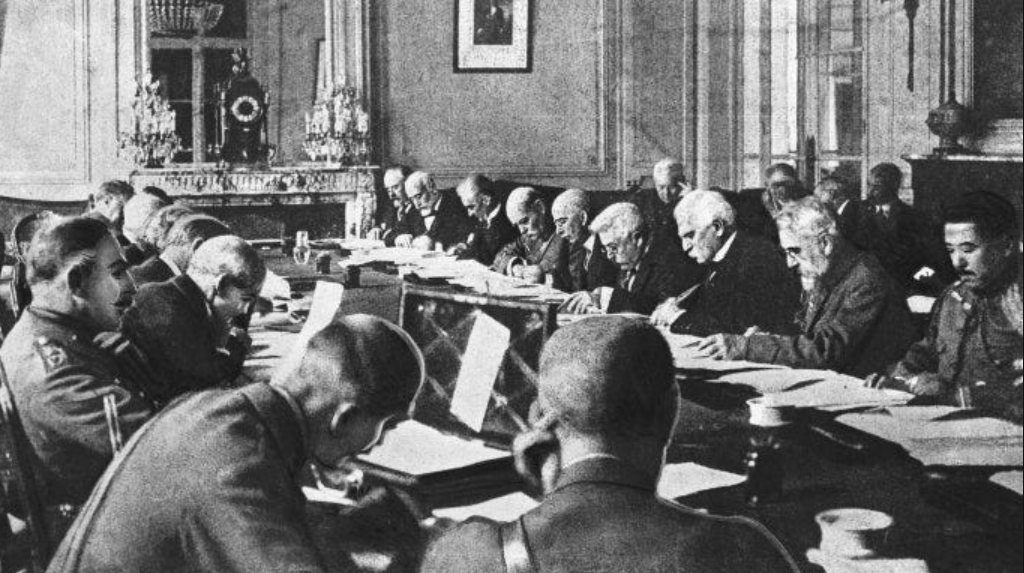

The military scale of the conflict has not reached – and we hope it will not in the future – the destruction wreaked upon the world by the First World War. Idealistically termed “The War to End War”, its aftermath never indicated that this would be a realistic name.

Guided by self-interest, vengeance and naivety, America, Britain and France all insisted on utterly different provisions.

France hoped that Germany’s power would be dismantled, that its military would not nearly be capable enough to challenge French continental superiority for decades.

Britain did not see a need to be so ruthless with the terms; it simply desired for Germany’s ambitions to be more subtle, and for the country to remain a second-tier power.

America’s position was by far the most lenient; the country being untouched by war and its economy swelling may have induced a degree of bias.

This shambolic concoction of opinions led to a Treaty of Versailles that British officer Archibald Wavell, who would later become a Field Marshal, described as a “Peace to end Peace”.

Two key representatives agreed that the resulting treaty was a poor piece of work that was not sufficient to maintain lasting peace after such tragic events.

John Maynard Keynes of the British Empire – a man whose work would make him the most significant economist of the 20th century – thought that the economic repercussions for Germany were unsustainable. In particular, though, he was worried about the insulting impression that the Treaty would have on the German population, and the substantial hatred and resentment that this would develop.

Conversely, Ferdinand Foch, a decorated French Field Marshal, believed that the Treaty was not punishing enough, and that Germany would eventually attempt to lash out again regardless of the Treaty – not due to its terms but due to the country’s will to avenge their ‘undeserved’ loss.

It is interesting, then, that they were both partially correct. Whether a different approach to peace would have actually been successful only history could have told; both individuals’ evaluations that the provisions would fail.

The result was an incomplete Carthaginian Peace.

Taking its name from the terms imposed on Carthage by Rome after the end of the Third Punic War – which had resulted in a crushing defeat for the North African empire – it constitutes a treaty that virtually eliminates the losing side’s ability to compete. The aim is to prevent a future conflict but, in actuality, often has effects equivalent to occupation.

This is why the Treaty of Versailles was an incomplete Carthaginian Peace. Despite its severity, it did not fully liquidate Germany’s capabilities or its potential for a resurgence.

The decisions faced by Western leaders, as well as those less aligned, undoubtedly relate to those made following the First World War and will rely on centuries of diplomatic thought and experience.

Three broad possible approaches exist following the end of the Russia-Ukraine War.

The first is the most balanced approach, advocated for by leaders such as Rishi Sunak, the British Prime Minister. It would involve leaving sanctions in place, pursuing reparations and potentially trying to reintroduce some level of communication. It would not strive for further punishment to be imposed on Russia.

The second is the approach desired by ‘frontline’ nations such as Poland, the Baltic States, and, unsurprisingly, Ukraine. The strictest possible way forward, it would constitute a continued effort to ostracise and isolate Russia from the world. In addition, it would try to wean China and India (among other, smaller economics) away from Russia and try to convince them to end the financial support they provide to Putin’s regime primarily in the form of weapons and oil purchases.

The third is a doctrine no politician has yet dared properly voice, unquestionably due to the backlash they would instantly receive: deescalating tensions, reducing the economic distance through the thawing of sanctions, and achieving dialogue with Russia. This would probably be a manner favoured by countries such as Emmanuel Macron’s France or Olaf Scholz’s Germany; the former’s corporations had an immense presence in Russia (and have mostly still not withdrawn) and the latter used Russia as a cheap and fairly reliable source of energy. Of course, for Germany to return to reliance on Putin’s regime for the supply of oil and gas, vital commodities despite endeavours to phase them out, may seem shortsighted and foolish but it is vastly more affordable than developing a large enough domestic renewable energy industry or purchasing from the Middle East.

Each of these approaches would carry their dangers.

Resuming trade with Russia could directly fund another attempt to invade Ukraine or another NATO-aligned country. In fact, such a path could lead to the West being so inclined to avoid war and maintain the idealistic peace that would be created that they would then pursue a policy of appeasement (and history does not remotely look positively at this).

Simply ‘leaving Russia alone’ could still fail to prevent the fostering of hatred within the country and fuel the population’s approval of another attempt to invade Ukraine or another NATO-aligned country.

Increasing the severity of sanctions and isolating Russia to even greater extent with the aim of stymieing its economic and technological development – the approach most closely resembling a Carthaginian Peace – would certainly strengthen Russian opinions that the West despises them and seeks their country’s elimination and could spark the population’s insistence on another attempt to invade Ukraine or another NATO-aligned country (or to go even further).

The fact remains that whether a Carthaginian Peace is the intent or not, its most dangerous feature is the cultivation of resentment. Unfortunately, since the occupation of Russia is neither feasible nor wanted by any Western nation, the Kremlin’s control over all aspects of information will mean that such feelings of resentment will definitely continue to flourish.

The only alternative would be the deposition of Putin’s regime, something that is unlikely but not strictly impossible.

This possibility will be discussed in the next article.

Originally Published on the Author’s Medium page

Leave a comment